I entertained my very first thoughts about homeschooling shortly before I got married, but years before I even had any of my own children. These thoughts surprised me; I’d gone to public school all my life and had never, not once, never ever, considered anything else for my future family. Why should I?

And then I got a job at a public elementary school. Hence, I opted for homeschool.

I don’t want to misrepresent my job at all; in fact, it was my favorite job that I’ve ever had and I loved working there! I was a literacy aide, which meant a bulk of my job was teaching small groups of below-grade-level readers to help bump their reading scores back up. It was wonderfully rewarding and I felt very useful and important. I also loved my coworkers and I sorely missed my fellow aides after I left. I worked with a great team and we had an amazing and supportive boss. To top it all, I saw firsthand so many incredible teachers who were passionate and caring about their students. I really loved my job!

That being said, I had enough troubling experiences that made me rethink both my own public-schooled childhood and my assumed decision to public-school my future children. Still, I remained on the fence about the topic for many years, as I didn’t have any children at the time to actually homeschool.

But here we are, years later, and I’m finally facing that decision. My oldest will start kindergarten next year and now I actually have to decide: will his school be down the street or here at home?

Spoiler alert: If you couldn’t tell by the title, I’m super on the homeschooling side now. It’s a little intimidating, yes, but I’m pretty firm in that decision, at least for his kindergarten year, and then we’ll keep pushing forward as our situation allows.

I wouldn’t argue that homeschooling is divinely flawless while public school is irreversibly evil. On the contrary, my work experience and my personal research have reiterated to me that either can work great for certain situations. Some people simply may not be prime homeschool candidates or aren’t in a situation to do so, and instead thrive at public school. That’s great.

But I, in my indecisiveness, did the best thing I know how when faced with a difficult decision: I wrote about it. And the following pros/cons list is what I’ve come up with.

Brace yourself.

Reasons to Public-School:

Social:

Because it’s NORMAL.

Yep. You got me there. I have no rebuttal for this one. Homeschooling would be a big jump out of my comfort zone and could potentially alienate me and/or my children from other people who’d be put off by our abnormalness. It’s a truth of human nature that we like the comfortable and the familiar, and indeed public school is both of those to our society at large. We’d fit right in.

But do we really want to? Think about it.

My children might respond better to an outside authority than to me, their mother.

It’s a real issue I’ve pondered, but I don’t like the fact that it exists in the first place. I would hope to parent in such a way to garner respect and obedience from my children, but I’ve heard time and time again that children often behave better for friends and strangers, not having that same guarantee of love and acceptance as they do from their parents.

I can justify that outside authority figures will still exist for my children: church leaders, piano teachers, coaches, etc. But regardless, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t worry about this issue.

My children would learn social norms and basics such as sitting at a desk, standing in line, asking to use the bathroom, raising their hand, etc.

For a while this one really bothered me. But then one day I had a conversation with my friend who was herself a public school first-grade teacher (at the time). She confided in me that she was having some difficulties with one of her students who’d been homeschooled the previous year. At first my stomach just dropped; it was all my worst fears, that homeschooled children are weird or difficult or something. “What’s wrong with him?” I asked, assuming the worst, “Is he a weirdo?”

“Oh no,” she responded, and said that he got along very well with the other students without a problem. But he “didn’t know how to school,” she said. She said that he was constantly up and away from his desk, would leave to use the bathroom without asking permission, and struggled with the concept of rotating at the ding of the bell and instead wanted to stay where he was until he had finished his current work.

“Oh,” I answered upon hearing her list of grievances. It wasn’t at all what I expected and wasn’t nearly as bad. But it got me pondering: what is the purpose of learning those social skills like raising your hand and walking in a straight line down the hallway? Those are school-specific skills, not life skills. No adult employee (that I know of) has to raise his hand and ask to use the bathroom at his workplace, or walk down the hallways in a straight line and with his arms folded, or would get punished for standing up every now and then to stretch his legs. These particular “social” skills that I was so worried are so vital aren’t actually “social” at all: they are school skills. And once school is over, what is the purpose of these skills?

Sentimental:

So I can take those cute “first day of school” pictures on our front porch with them holding signs that say their new grades and teachers’ names.

So I can go to the annual Halloween parade.

So I can be the volunteer mom and help in the classroom with art days and holiday parties.

These might sound silly but they really do hold a place in my heart. After all, this is how I grew up, remember? My mom was this kind of mom, the volunteer classroom helper, and it was the kind of mom I always planned to be.

But with homeschool I’d be way more than a volunteer classroom mom, I’d be a homeschool mom! As for holidays and stuff, I guess it’s all the more reason to make them special at home with our own family. There’s no reason we can’t still have a Halloween party or still celebrate MLK Jr. Day by sleeping in and doing nothing.

But that’s the extent of my pro-public school list. Let’s move on.

Reasons to Homeschool

Academic:

To avoid testing, all of the testing!

When I was in school we strictly had end-of-year tests. Other than those few difficult weeks in May, I remember very little standardized testing; we actually did schoolwork in school. Shocker.

Not so much anymore.

Kids in public schools are tested all the time throughout the school year. There’s luckily been some hopeful backlash against it, but that hasn’t changed the endless, relentless testing. Whether it all started with the No Child Left Behind Act from the Bush administration or the Common Core during Obama’s days, the bottom line is still the same: we are over-testing students.

And I don’t like it.

When I worked as a reading aide, part of my job was testing monthly reading levels. We were constantly testing, constantly updating charts and lists, and constantly watching scores. And guess what all that testing showed? Basically the green kids (on-level) were always green and the red ones (below-level) were always red. Maybe if you quit wasting time testing and actually let the teachers teach reading, then those poor red kids might actually stand a chance!

Besides the sheer amount of testing, I came to dislike the tests themselves. I didn’t think they were very indicative of the truth or very helpful in general.

I most often gave kids a one-minute fluency test. We timed the kids and marked how far they read a certain passage, marking all the words they got wrong along the way. Then we counted up the number of their correct words and that was their score.

But I found this test horribly flawed. For one, kids who actually read well and had really good fluency knew that fluency isn’t just about speed, but about comprehension. They’d read the passage slowly enough for a listener to understand; they’d emphasize the correct words and read with passion and emotion. They were great readers and a joy to listen to! But all that niceness slowed them down and they didn’t score very high.

Other kids figured out that the system wanted a number only and so they threw all expression and punctuation out the window; they read like speedy robots, hardly pausing for a breath even between sentences. They often made mistakes along the way, but never noticed or never cared because they knew that the final number was the only important outcome. And they were right. And they did indeed score really high, but that didn’t mean it was a particularly good reading of that passage.

On the other end, the poor slow kids would get stuck trying to sound out a word. We were instructed to let them try for ten seconds before giving them the answer, marking it incorrect on their test and moving on. The slowest readers often scored a big fat zero, not because they couldn’t read or couldn’t sound out the words (sometimes they simply couldn’t read either), just because they just took their sweet time and were mega slow at it. That was always sad to mark.

Or you’d get the curious kids who’d come to a new word they didn’t know. Whether they sounded it out themselves or I finally told it to them, I’d often get kids who stopped reading, looked up at me, and asked, “What does ___ mean?” It broke my heart to shut them down; I had no other choice. I had to force them to keep reading, to speed through it; it didn’t matter if they knew all the words, they just had to read them! But I always felt like I was squashing a curious little spirit, punishing them for asking questions. They should ask questions! They should clarify! They should make sure they fully comprehend what they’re learning! Those are the signs of a good reader and learner, not just an arbitrary number on a chart.

And this was all for that single, one-minute fluency test.

Besides not being a very good test, the testing itself added a whole different layer of trouble: the the slow kids always felt bad about themselves. Kids catch on to more than you give them credit for; the “dumb” kids genuinely knew they were dumb, and all the tests were just a constant reminder to them that that’s what they were: dumb. It was a blow to their self-esteem every single time. And I hated that.

The final straw, for me, in regards to the endless testing, was about a particular girl in second grade. She was an extremely poor reader. By the end of the school year she barely had a few sight words down and was only just starting to sound out words, but definitely she wasn’t actually reading. (As a literacy aide I mainly worked with kids who were only just below grade level; anyone lower than that was sent to Resource for more drastic help, as was the situation with this particular girl.)

As the school year came to a close, I thought of her moving up to third grade at such a dismal reading level. I knew she was destined to be in Resource essentially for the rest of her entire schooling career. She also had those self-esteem issues and often refused to even try reading during our tests. “I’m too stupid to read,” she told me on more than one occasion. It really broke my heart.

And what’s worse is that we were helping first graders master her exact reading level; she needed the remedial first grade help! She definitely didn’t need the remedial third grade help that she would get the following year, because even that didn’t go back as far as she needed. Yep, I was afraid that she was totally doomed.

Her test scores all showed this, of course, and I finally took them to my boss to ask about her. “What can we do for her?” I asked desperately. “She needs first grade level work! Can they, I don’t know, hold her back a grade or something?” Even the remedial second-grade program would have been more useful to her than the remedial third-grade.

“Oh no,” my boss answered and then she delved into some very unfortunate politics talk. She said that as a public school, the government will allow (pay for) students to go to school for thirteen years, kindergarten through twelfth grade, and no more than that. If we hold this girl back then she’d get fourteen years of schooling, which the government just wasn’t willing to pay for. “The only way a kid ever gets held back is basically if the parents throw a really big stink about the whole thing, like they have to appeal to the district and everything,” she told me, “And most parents don’t want their kid to be held back anyway, so they’re not willing to do it.”

I was really upset and felt really useless. So this poor girl was destined for failure the rest of her life. Forever she’d think of herself as stupid and she’d always be at the very bottom of all her classes because she couldn’t freaking read!

But then a furious thought popped into my head and out my mouth before I could stop it. “They won’t hold anyone back based on their test scores? Then what’s the point of testing them so much!?”

My boss seemed a little taken aback and said that the testing was important to track students. But that wasn’t a good enough reason, in my opinion. Why track them if you do NOTHING with that information? Why track a constant stream of zeros from this poor girl if you refuse to raise a finger about it? WHY ALL THE STUPID TESTING!?

To avoid nutcase-crazy kids.

This sounds harsh and that’s because it is, but it remains true. When I worked at the elementary school I saw way too many instances of wild, out-of-control kids essentially running violent dictatorships over their classrooms. I might guess that there was at least one of these kids per grade (four classes per grade in my school), so of course you might get lucky and miss out on the uncontrollable psycho kid, but if you weren’t so lucky then the outlook was bleak.

The mild Nutcase Crazy kids (according to my personal scale) were simply mega jerks who were always disruptive and rude and who purposely derailed any and all lessons just for the sake of it. You might call them class clowns, but that’s too nice. I’m talking about kids who purposely wreck lessons and activities for everyone else around them. They most certainly exist and their antics get really tiresome really quickly.

On the extreme end of the Nutcase Crazy scale, you find kids who have diagnosable behavior disorders, kids who need medication, or who need to be in the special needs class but whose parents refuse to do either. Some of these kids were downright dangerous and violent.

I hate that I saw these cases as often as I did. And the thought that always came to my mind was this: what about the rest of the class? This one, wild, uncontrollable, nutcase-crazy kid takes 75% of the teacher’s attention, and then she only has 25% left to give to twenty other kids. I’d hate for my child to be a normal kid in that class and his academic needs get shunted to the side just because Mr. Nutcase went berserk again and wrecked the lesson (or the entire classroom) again.

So that if my children are below- or above-grade level, they will get personalized help instead of getting screwed over like they would in public school.

Yes, I very much think that public schools are geared toward exactly average students. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, especially for those average students. In fact, one might argue that public schools are designed for exactly average students, and I’d agree with you.

But what does that mean for extra low students or extra high ones? They get the shaft, that’s what.

Let’s start with the extra low kids, such as the second-grade girl I talked about above.

I taught a remedial reading program for kids who were one only grade-level behind. Kids who were two grade-levels behind or farther were sent to Resource or, in super drastic cases, Special Ed. But how do you get a kid into Resource? Testing, of course! It’s always about stupid testing with public schools. Testing and waiting, that’s how you get into Resource.

Getting into our remedial groups was easy; all a teacher had to do was look at recent grades and they could decide on the fly if a kid should be in our group or not—no extra testing required. Most kids were there long term, or some only a few months before they got back on track.

But to get a kid into Resource the teacher had to give them all sorts of special tests to prove they were indeed far enough below grade level to warrant Resource. Then they’d submit their tests to the administration who sent them to the district. And then the waiting game. Finally, often months later, some big wig from the district came and retested the low kid to be super sure they really needed that help, and then after that the kid would be approved and sent to Resource.

But here’s the kicker: if the district big wig retested the kid and found any improvement since the teacher’s previous test, that kid could easily be denied Resource help. Resource is all about the money, after all, and the district doesn’t want to waste any of that precious cash to pay those Resource super-specialists unless the kid really, really needs it.

So how did (some) teachers combat this? They taught their super, super low kids nothing. I wish I were joking. I often got Resource-hopeful kids dumped into my remedial group with the instructions to “just let them sit there.” It was imperative, for the child’s own long-term good, that they didn’t improve for the few months in between the teacher’s and the district’s tests.

Seriously, oh how I wish I were joking.

(A side note: all my information on this topic was told to me by coworkers and teachers and therefore I acknowledge it might be inaccurate; I myself never had to go through this grueling process of testing and waiting, so I can’t say how accurate it is. All I’m reporting here is my own experience, and this is what multiple teachers told me.)

What a waste! What an embarrassment! What an absolute disgusting disgrace! And remember when I said the slow kids know that they’re slow? Yeah, those Resource-hopefuls totally knew that they were dumb, and they knew they were too dumb for our remedial groups too. Talk about tragic.

That’s how the Resource kids get the shaft; let’s talk about how the advanced kids get the shaft.

Besides the remedial reading groups, my other main duty was teaching rotating groups during Power Hour. The class was divided into four groups based on reading level and rotated every fifteen minutes to different stations for some kind of language arts lesson or activity. One was with an aide like me to study vocabulary. The on-level kids had a few independent rotations, while the low-level kids did their remedial reading group work (again with another aide like me). And of course each group rotated to their teacher for fifteen minutes; this was the only time the kids got reading-level specific instruction, for that fifteen-minute group with their teacher.

I was constantly looking for ways to help the low-level readers, and I started theorizing on a radical new schooling idea to help students. If low-level kids (and on-level kids too) benefited from level-specific learning for that fifteen minutes, why not teach level-specific material all the time?

Our school had four classes in each grade; why not divide the classes by level and have a Resource class, a below-level class, an on-level class, and an advanced class? Then the Resource level kids could go over old material and move through the lessons as slowly as they needed to make sure no one got screwed over for their entire lives. Meanwhile, the advanced class could move forward as quickly as they wanted and even cover above-grade material if they kids were up to it. Why not? I wondered.

Obviously I had no power to bring such a radical change like this about, but I brought the idea up to several coworkers more as a thought experiment. I was shot down over and over. First, everyone cited the fact that the Resource class and low-level class would know they’re the dumb classes and would have low self-esteem because of it. That’s a totally valid argument, yes.

“But they already know they’re the dumb ones!” I tried to counter. “They already have low self-esteem! The point is to change that, to help them move up and out of the Resource class!” Still, no one would hear it.

But the second answer downright upset me, both from aides and teachers alike. One particular teacher told me this: “But the advanced kids help the low ones so much! I purposely seat my highest kids next to my lowest so they can help them.”

“But shouldn’t they be free to advance if they’re able?” I asked.

“Why should they?” I got the answer over and over again. “They’re already above grade level. They’re fine.”

They’re fine.

Hear that? If you are exceptional in any way, shape, or form, don’t bother pursuing that. Just don’t bother.

You’re fine.

Don’t expand your horizons. Don’t push yourself. Don’t try for anything greater than what you already are.

You’re fine.

I realized, after this conversation, that this exact thing happened to me when I was in school. I was always near the top of my class as I was an excellent reader (math wasn’t my particular strong suit, but I’ve been a super reader for essentially all my life). And, upon hearing this answer, I suddenly remembered my own childhood and how frustrated I was when I had to sit by a slow kid. I suddenly remembered being continually bothered by the other kids around me asking, “What? What are we supposed to be doing? What? I don’t get it! What?”

All I wanted was to be left alone and read my book! Often when we finished our work early we were told to read silently until everyone else was done, which I loved to do. But I hated being interrupted by my fellow students. “What? What? What? What?”

And now, as an adult, I’ve learned that some teachers assigned their students’ seating that way on purpose! I was constantly bothered and annoyed on purpose so that I could be this little peer tutor to the kid sitting next to me? Well guess what–I didn’t want to be a little peer tutor to the kid sitting next to me. But I didn’t get a choice in that, did I?

That’s when I realized the other big flaw with public school: the advanced kids get the shaft too. So the advanced kids are purposely kept on par with their low-level peers? They don’t even get a chance to move forward, to advance, to shine? If they truly are exceptional, then why not let them advance? It’s not their job to be tutors and not fair to hold them back from their true potential. But no, that was totally out of the question. Besides, they’re fine.

Basically I learned this: public school is ideal if you are a perfectly average, exactly on-grade-level student. There you go.

To learn at your own pace.

Yes, this is a direct homeschooling-solves-this answer to the above issue. Instead of being trapped in learning grade-level material only, you could learn and move through material at whatever pace you want.

I remember being a first-time mom and constantly worrying about my son hitting, or not hitting, his big milestones on time. Of course I wanted him to be a super genius in all things all the time, so when he was even just a little off I worried and worried and worried (I like to think I’ve moved past that needless worry now with Baby #3…mostly). It was hard for me not to compare him with other babies we interacted with; was he crawling late? Walking early? Talking late? Pinching his Cheerios with his forefinger and thumb appropriately on time? It turns out that he’s a perfectly normal little boy and I love him with all my heart no matter what age he was crawling or walking or whatever.

I was slow to learn this vital lesson, but learn it I eventually did: children develop at their own pace. And as I researched homeschool, I learned that academic development is no different: children will learn to read when they are ready to read.

Now take that vital piece of information and hold onto it with me for a moment. Now dump twenty children, all ranging in barely-five to almost-six-years-old, into one kindergarten classroom. And start testing them. Grade them green, yellow, or red. Keep doing that. It doesn’t matter their developmental ability, and it doesn’t matter if one is eleven months younger than another; do the exact same thing for all of them, test them relentlessly, and grade them constantly.

Whatever happened to “develop at their own pace”? I guess public schools never heard that.

Reading was always my strength in school; I could have easily read and studied books several grade levels above my own, which I only ever did on my own time. But I was perfectly average at math; it was the only non-honors class I took in middle and high school. If I’d been homeschooled, I could have soared above and beyond with my reading while stayed a bit longer on the math that I needed. Or, if a child were particularly struggling with a certain subject or concept, you’d have the freedom and time to go back and thoroughly review that material. Wouldn’t that little second-grade girl certainly benefited from something like that?

But in public school you are dragged on at the exact same pace for every single subject with every single one of your peers—no speeding up, no slowing down, no backtracking, and no advancing.

To follow student-led interests.

One of my very first thoughts about homeschooling was the huge benefit of following my children’s individual interests. It’s not a mystery that people of any age are more engaged and excited to learn about something that interests them, particularly if they chose that topic themselves rather than being forced into it.

Does my kid like to read Percy Jackson? Great, let’s study Greek mythology. Is he into computer programming? Great, let’s find a program for that. Does he want to study animals? Great, let’s hit the zoo!

Fantasy novel writing? World War 2 airplanes? Dinosaurs? Choral singing? Video editing? The inner workings of beehives? Painting? Ancient Egypt? Whales? Trains? GO FOR IT!

Heck, even if my toddler says he wants to learn all about pirates then by golly we can learn all about pirates!

There is nothing stopping my child from pursuing his passions and interests with homeschooling, and that’s a beautiful thing.

To not waste so much of the day.

I already talked about how public schools waste time with testing, which is a whole different can of bananas in and of itself. But the rest of a typical public school day also wastes so much stinking time!

Specifically if you’re an on-or-above grade level student, think of all the times you finished a test or a worksheet before a bulk of your classmates. What did you do with that free time? Wasted it, right? You sat around waiting, you doodled on paper, or maybe you got into trouble by distracting your classmates. Best case scenario, you read silently. I remember silent reading a lot when I was in elementary school (my brother, however, was always the one who distracted his buddies; we’re very different, he and I), but then I’d always get annoyed that I had to stop reading when the rest of the class was finally done and ready to move on.

In other cases besides finishing schoolwork early, think about how much time is wasted in those little moments throughout the day that wouldn’t exist in a homeschool environment. Take the morning classroom routine of hanging up your backpack, turning in your homework, marking your attendance, making a lunch choice, listening to school announcements, and then most likely starting a busywork activity that’s purpose essentially is to give you something to do while the rest of your slowpoke classmates come in and make their lunch choices as well.

I remember in second grade we had to write out the numbers 1-100 every morning when we first got to class and I thought it was so unbelievably boring. None of that exists in homeschool.

Busywork falls under this category. Oh, how I despise busywork. Nothing more wasteful exists in the world. Even at a young age I recognized busywork when it was handed to me and hated it. It was so demeaning, like I had to be babysat by a stupid worksheet.

I had a particularly horrible fifth grade teacher, which was the year we were supposed to study all the states in the U.S. Every day we got a word search shaped like a particular state that was filled with words describing it, usually lists of common exports, important locations, and points of interest. These word searches were so overstuffed that to find all the words used up nearly every single letter on the board. It was the “cool” thing at first to compare your word search with your friend and make sure you had the same two or three leftover letters in the same tucked-away corners of the page. As the weeks went on and we got insanely bored with the endless word searches (which aren’t very informative or interesting to begin with), the later trend was to just color in every single square except for a random few along the very edges and corners and turn it in without bothering to do anything else. Yep, it was busywork at its finest, and a great excuse for our lazy teacher to not actually have to teach us about any of the states. What a monumental waste of time!

Then there’s the time wasted in changing activities, in cleaning up, in putting things away and getting things out, in lining up, and in waiting for the stupid class clowns or nutcase-crazy kids to get it together. It takes time to walk down hallways to get to your special activities, to wait for everyone to grab their lunchbox, to wait for everyone to meander through the library after you’ve picked your book within the first five minutes you arrived there. Sure, you’d spend time switching between activities at homeschool, but at least you’re not at the mercy of your slow classmates for every single little thing. How utterly aggravating!

One of the most encouraging things I read about homeschooling routines is that they typically take significantly less time than public school. I’ve been looking specifically at preschool and kindergarten curriculum and routines and almost everything I’ve looked at says that it should take less than an hour a day. It really makes me wonder what on earth they’re doing in public school that quadruples that time, even for half-day kindergarten. The answer I keep coming back to is this: you’re waiting for other people, which is just the pits. In homeschool you do what you have to do at the pace you want; no waiting and no wasting time. Then there’s so much more time for kids to be kids and to actually enjoy being a child.

To not do homework.

Yes, all of homeschool work is “homework.” Ha ha! But seriously, remember all that stuff I said about wasting time? In so many ways, I think homework is also a waste of time—a majority of it is just busywork. Obviously I’m all into reading with your kids every day after school, that’s a given, but honestly until middle school or possibly even high school, I don’t see much point to homework. School is already freaking seven hours long! How wasn’t that enough time for you? You’ve already taken my babies away for most of the day! Now you want to take away my evenings with them as well? Where does it end with you people?

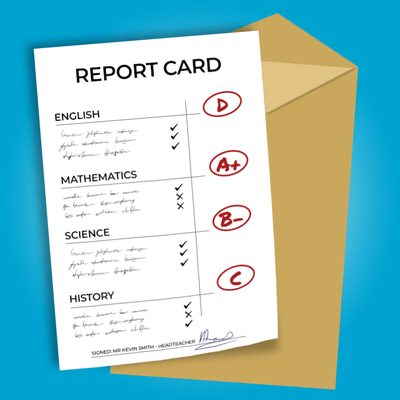

To not worry about grades.

Controversial opinion right here: I don’t believe in grades, very much in the same way I don’t believe in testing.

Hear me out. Just like with testing, we test and test these poor kids and then do nothing with their test results. And then we grade them. And likewise do nothing with those grades.

Theoretically we should do something with those grades. If a student fails all their math tests all the time, someone should probably stop and think, “Huh, maybe this is too advanced for him. Maybe he needs to backtrack and review some earlier material. Maybe, maybe, maybe…” (See my note above about learning at your own pace.) But there’s no time for any of that in public school.

Yes, I understand that high school grades are one of the few tools that potential colleges have to assess applicants, so high school grades and transcripts make total sense for college-goers.

But middle school grades? Elementary school grades (especially elementary school grades)? I don’t think so.

Going along with the earlier note about following a child’s personal interests: a child will thoroughly study, enjoy, and retain information they are passionate about. No grades necessary! And no test necessary either, by the way.

Further, grades aren’t always accurate.

I rarely needed an actual test to know whether or not a child could read well; basically as soon as you pass them a book you’ll figure out really quickly how well they can or can’t read. And so it goes with grades. Grades aren’t always accurate representations of a student’s academic stance. They might be failing everything out of laziness, but not because they don’t understand the material. Or they might be getting good grades simply through good class participation, but may not necessarily understand everything thoroughly. I even worked with a few dyslexic kids in my time who had perfect comprehension of verbal lessons but had failing grades all over the place because of their learning disability.

(That was always super heartbreaking, because those dyslexic kids, more than any other students I worked with, very genuinely thought they were stupid. Shout out to all dyslexic students (or whatever learning disability you struggle with) out there: You are not stupid!)

The bottom line is this: grades aren’t a tell-all or solve-all solution, and therefore I don’t think they’re necessary (except for the college applications, as mentioned above).

I remember in middle school getting full-blown anxiety about my grades. Most of my friends were 4.0 students, and most of the time I came in around 3.8. Normal people would look at that and say that’s great, right? But not for me. I’m too darn competitive and too much of a perfectionist.

I wasn’t a bad student or a dumb one, not by any means, but I was just lazy. My biggest problem was that too many of my assignments stayed lost in my folder instead of getting turned in. Whenever I saw my report cards I’d have to frantically dig through my folders and locker for all those missing assignments that I’d simply forgotten, and then of course only get half credit for turning them in late.

I always dreaded the end of every quarter when I’d frantically scramble to turn in the missing assignments I’d forgotten. And my skin would breakout terribly because of the added stress.

Looking back, it was such a waste of anxiety! What a waste of breakouts! And it really put a damper on my confidence and overall school experience. Every single quarter I’d promise myself I’d do better and stay on top of things; after all, so many of my friends got those 4.0s without breaking a sweat! What was my problem? And then every single quarter I’d mess up, forget more assignments, and inevitably get a stupid A- in some class instead of my perfect A, and then my whole report card was ruined!

I don’t want my kids to have to experience this, to base their entire self-worth on a letter on a sheet of paper. Or even worse, to feel like they failed because they were this close to perfection but only just missed it by a few stupid points, as I always felt.

I want my boys to genuinely enjoy learning, exploring, and discovering; I don’t want them to dread school and get anxiety and breakouts over something as meaningless as grades.

To dictate our own extracurricular activities.

More and more public schools are limiting extracurricular activities, namely art, P.E., music, and recess (yes, I very strongly believe that recess is super important!).

But in homeschool we can do as much or as little of those sorts of activities as we want. We can exercise and play outside every day. We can sing songs and play the piano. We can make an art project whenever inspiration strikes. We can do it all, or pick and choose our favorites. Learning is supposed to be fun, and one way I plan to make learning fun for my children is through these types of activities.

As my children aren’t elementary school age this year, I obviously haven’t been forced to deal with the sudden nightmare of online/distance learning due to a pandemic that so many parents were thrown into, and for that I’m very grateful.

Regardless, I was still comforted to read a homeschooler on Facebook post this: “Quarantine-schooling” is NOT the same as homeschooling; homeschooling is supposed to give you MORE freedom to DO things such as visit museums and parks, learns in group co-ops, play on teams, etc. Locked-down quarantine-schooling, therefore, is the antithesis of homeschooling. Homeschooling means freedom.

Familial:

To not have crazy, hectic mornings.

I think it’s like this standard, expected thing that in order to be an American family you have to have crazy, hectic mornings with kids crying about not being able to find their shoes, spilling breakfast all over the place, frantically tying shoelaces and zipping up coats, then throwing everyone in the minivan and racing very dangerously to school because you’re late. Yep, that’s just the norm.

But why? I don’t want to live like that. And I don’t want the last image that my boys walk away with every morning is me all frazzled, crazy, and yelling at them to remember to turn in their homework and to take their lunchboxes and to put on their coats. That’s not the kind of mom I want to be. That’s not the kind of mornings I want to face for the next two decades.

If we homeschool, mornings won’t have nearly the same kind of rush. I can encourage (require!) kids to clean up their own breakfast dishes. We can do chores and daily tidying together before we start our schoolwork as part of our routine. We can get dressed and brush our teeth and handle whatever the day wants to throw at us peacefully and calmly—it’s not nearly as horrible to start a homeschool day late because someone was sick or spilled breakfast or whatever, than it is to be late to public school.

To dictate my own family’s schedules, holidays and vacations.

Just like I hate the idea of schools dictating how my mornings ought to be (crazy, hectic, and unhappy), I also hate the idea of schools dictating how my vacations and holidays ought to look like, namely when and how long they are.

If we want to lighten our schoolwork during the entire month of December in order to enjoy some quality Christmas time, by golly we totally could if we homeschooled. If we want to take a vacation in October to southern Utah to capture the last of the warm weather, by golly we could do that too and not miss out on any school things either.

We had a rough night and need to sleep in? Done. We want to schedule all our schoolwork for Monday through Thursday? Done. We want to not start school until after Labor Day? Done. We want to start our summer vacation on Memorial Day? Done. We need a day off for a family emergency? Done.

Further, we could totally continue doing all the summer and holiday things during school hours, so campgrounds, vacation destinations, hikes, swimming pools, parks, etc. will be virtually empty, instead of trying to fight the school-vacation crowds everywhere we go. Let all the public-school crowds go to southern Utah over fall break; we’ll go the week after and miss them entirely.

To control our own sick days.

If there is a particular public-school policy that really makes my blood boil, its the one that says students have to have a signed doctor’s note to prove that they are sick.

I am not wasting my time and money to drag my sniffly kid to the doctor, wasting his time and spreading our sniffly germs all over that office and exam room, just to get him to say, “Yep, he’s got the sniffles. It will go away in a couple days.”

No, no, no!

School administration demanding that kind of proof is just laughably stupid. It’s stupid.

I am the parent. I know when my child is sick. The school is subject to me and my decision whether or not he is healthy enough to go to school, not the other way around. End of story.

Gosh, this is making me mad!

But think about sick days in a homeschool setting. It’s a huge bummer to miss a few days of public school for something as mild as the sniffles or a little cough, and then be swamped with extra homework and makeup work after the fact. But none of that is a thing when you homeschool!

On days with the mild sniffles, you can still do your schoolwork and not be behind. If your sickness is more severe, you can have a calm reading day or movie day and still not be behind. Heck, if your kid catches something super awful and is in bed for weeks on end, you could even take a break entirely from school as necessary and pick back up where you left off as soon as he recovers. Lovely!

To spend time with my kids.

I’m not making this up. I genuinely love being with my babies, and I plan and hope that love continues as they grow. I really hate the idea of giving my kids away for a bulk of the day and missing out on all their daily successes, trials, and excitements. I’m their mom! I should be the one who gets to spend every day with them, not some random stranger called “teacher.”

So my family and kids will spend time with each other and be friends with each other.

I’m not trying to say that my family will be perfect and every moment of every day will be all sunshine and rainbows. Families disagree, siblings fight, tempers flare, and people snap sometimes. We’re all human, after all. Heck, my boys are only four and two and I already moderate toy-sharing between them all day, every day! Sometimes it’s all I do from breakfast to bedtime and it’s exhausting!

But…I want my kids to share their happy moments together as well as their hard ones. Not only do I want to share in their excitement and successes, I want them to share and enjoy each other’s as well. I want them to use the bulk of every day building our family relationships, not spending time with family last after a long, boring day at school.

To get the best of my kids, not the crankiest.

This kind of goes along with the two previous entries. Everyone says that kids are cranky after school, and I believe it! I remember being cranky after school and I remember my brothers being cranky after school. School is so long and, frankly, boring, that it really will sap all the energy from a kid. If I send my kids to public school, I’d already be missing out on seven hours of their day; I don’t want my limited afternoon and evening with them to be filled with cranky, hungry, and overwhelmed kids. No, I want to enjoy being a mother and I want my kids to enjoy their childhoods. I want to experience the best and happiest parts of the day with them, not the crankiest.

To have fun!

Think of the freedom, the joy, the fun that homeschooling could be! Field trips, reading books, playing outside, making art, building things, doing science experiments. My kids only get one childhood and I want them to look back and have happy memories of growing up, of being with their family, and of loving to learn and discover new things. I want us to enjoy school and learning, not dread it.

Religious & Political:

So my boys won’t be targeted for being white, Christian males.

I’m a white person, yes. My husband is a white man and therefore together we produced white children, yes. I’m not ashamed of that.

When my firstborn son was about nine months old (and was our only child) my husband went on a business trip to Boston for a week. I went with him, just for fun, and we made a little family vacation out of it. While he worked during the day, I hit the streets of Boston with my faithful stroller and little baby. In the evening my husband joined us for the biggest, best attractions, and we had a wonderful week in Boston together.

But we had a rather troubling experience there. One evening my husband and I, with our baby in his stroller, walked to McDonald’s to grab some dinner. Outside the restaurant we saw a black man who watched us very particularly as we approached. When we got closer he shouted at us, “One of you should have been black, and then he would have come out looking like me! But instead all you white people have these recessive genes!”

It was very bizarre. In fact, it took me a moment to register what he’d even said. This guy definitely didn’t seem normal, like he was probably high as a kite on something or other. We walked right past him and he just stared and stared at us. It was very disturbing. And only after we got inside and sat down to talk about it was I able to sift through what he’d said and his meaning.

It really stung when I realized that he was insulting my baby, of all people. He was implying that my sweet, innocent little boy was somehow bad for being white, that he should have been black, or at least half-black specifically. It stung when I realized that my baby got yelled at, and I as his mother, by a random stranger on the street for no other reason than the fact that we’re white.

Well you know what? My child is innocent and his skin color doesn’t dictate his value. Yours doesn’t either, by the way.

It was my greatest fear, when finding out that my first child was a boy, that he’d be targeted, and that experience in Boston, as minor as it may seem, was confirmation of that.

And then we had another boy, and then another. White, Christian boys: my boys are everything that leftist radicals hate, just by existing!

But what does this have to do with school? Everything.

I refuse to send my child, my innocent child, to an institution where he will be drilled and brainwashed into thinking he is bad, the source of all evil throughout history, just because of his race, gender, and religion.

I refuse to send my child to an institution that will push ideas like “toxic masculinity” and “white privilege.” Instead I absolutely plan on teaching him that his masculinity is a strength, not a weakness, and that his skin color doesn’t entitle him to any special treatment.

Character. Character. It’s all about the content of his character and his personal choices. I want to raise my sons to be morally sound, independent, responsible, and strong enough to fight evil.

You might think I’m inventing this anti-white school scenario in my head. Surely I’m exaggerating, right? No teacher out there actually teaches this, right?

I was taught this. And I was raised and schooled in the very conservative state of Utah.

Granted, I don’t remember terms like “white privilege” and “toxic masculinity” existing during my school years. But I do have many distinct memories of a particular history teacher and the content of his lessons. I usually enjoy learning about history, but I remember feeling bogged down by his class day after day. Every single lesson emphasized that “white men” had caused whatever object of suffering we wrote detailed notes about that day. I remember my soul drooping a little and wondering if I was supposed to hate myself for being white, for being associated with such historical monsters as my teacher portrayed.

Wasn’t there ever any good history to learn about? Wouldn’t there ever be a lesson about a good man who simply managed to accomplish something awesome? If there were, I don’t remember those lessons; I was too overwhelmed by the bad.

In fact, I distinctly remember when we talked about women’s suffrage and I felt an odd bit of relief: suddenly I wasn’t so associated with the bad guy–I was a woman! Finally on the side of justice and goodness.

And then my sons were born. And I thought of that suffragettes lesson. Would my boys ever get to feel that relief? “Finally I’m not the bad guy!” At public school, no they wouldn’t.

Let me be perfectly clear: have atrocities been committed throughout history? Absolutely, an unfortunate amount of times, yes. But good has happened too, and I don’t believe in lumping all white people together as “bad” because of the evil choices of individuals.

And most of all, my boys, as white as they are, are not responsible for the actions of other people, past or present, white or black, male or female. They are responsible for themselves, and I won’t have them brainwashed into thinking otherwise.

The government is not my kid’s parent; I am.

There has been a rising and very disturbing trend lately where public schools (owned and run by the government, so therefore the government) are reaching farther and farther into homes and taking more and more rights away from parents. I don’t like this at all.

Mostly these are political moves to push leftist agendas. The most common is when “health” curriculum pushes too far into the realm of inappropriate because schools don’t trust parents to teach their children about sex at home. Even scarier, many school districts are pushing to remove parents’ freedom to opt out of such lessons. Some won’t give the parents any warning that such material is being taught in the first place.

And I’m a firm believer that sex and intimate relationships should be first and foremost taught in the home. That’s a parent’s first responsibility in ensuring that their child grows up to be a functioning adult. But the more schools push radical sex education, the less and less involved parents will be; why should they be involved at all, when the government will pick up their slack?

I can’t emphasize this enough: I am the parent. I get to decide what, when, and how my children learn about sex. It is my responsibility to teach them about sex, not the government’s. If my child really does enter adulthood as dangerously naïve and stupid as ever, that’s my fault as his parent, not the government’s fault nor is it their responsibility to correct.

A school in the Seattle area offers long-term birth control for girls as young as eleven without parental consent or knowledge. A school principal in Minnesota took her students on a field trip to a sex-toy store, again without parental consent.

Note the concerning trend: without parental consent. We can talk about the severity of the crimes committed here and their degrees of inappropriateness as a separate issue, but for the moment I want to focus on that one, glaring danger: without parental consent.

More recently, a Twitter thread went around where a teacher lamented how difficult the online learning is (due to the Covid pandemic) because he couldn’t trust that parents weren’t listening to his racism lectures.

That’s a huge red flag. If you’re telling your students something that you’re afraid or ashamed of their parents hearing then you are in the wrong, dude. Seriously, what are you saying that’s so dastardly? And even worse, who do you think you are, presuming to know so much better than those parents at home? Huh?

I am the parent. You are no one.

Stay the heck away from my kids.

Yes, parental consent is becoming a thing of the past. That’s a very scary thing.

I don’t trust teachers to not spout their political views.

Similar to the above issue, I have no reason to trust teachers; they are total strangers, after all. And I have no idea what they will preach or how they will preach it.

Notice I said “preach” and not “teach.” It’s an important distinction.

Teaching has become a weird profession, I think. Teachers used to be just that: teachers, responsible solely for teaching academic material. But there has been a growing trend of teachers being forced to transcend that role and become a Second-Mommy, for lack of a better term.

I can appreciate when a teacher rises to better serve and help a child from an unsafe or unstable home life, to be that child’s source of peace and emotional well-being. But that used to be the exception, not the rule. Mothers, as in actual mothers, used to be the primary source of all other learning, including the responsibility to instill emotional, religious, political, and moral values.

But now teachers are expected more and more often to become that Second-Mommy figure; it used to be the exceptional teacher performed that role, but now if you don’t do it, you’re suddenly a bad teacher.

Oh boy. I most certainly don’t envy modern teachers who have to try to wade through the political mess that teaching has become.

That being said, I wished we lived in a world where I could still be the mother and the teacher could just be the teacher. But we don’t. And I have to assume that teachers will, at some point or another, be put in a situation where they are forced to preach their personal moral and political views (whether or not they want to).

And I have zero idea what those personal views will be. I didn’t hire this person. I didn’t do any background checks. I don’t know what other groups this person is affiliated with. I don’t know what this person believes.

But somehow it’s normal for me to blindly send my child to spend a bulk of his day with this perfect stranger with zero idea of what she’ll preach to him. Seriously.

In fact, I knew a teacher personally (not one I worked with, but just a personal acquaintance who also happened to be an elementary school teacher) whose political beliefs became more and more extreme since I met her. She openly posted radical material on Facebook and shared how open she was about all this in her classroom. Eventually she quit teaching because she felt like the school was too “constricting” for her to share her beliefs. Yikes. I hate to think what kind of stuff she’d tell her students if she wasn’t so “constricted.”

There was an example in California a few years ago of a kindergarten teacher who gave her class a transgenderism lesson…without parental consent, of course. She read them a couple transgender books and then sent a certain little boy, who was himself a transgendered child, out of the classroom. When he returned, voila! He’d changed into a dress and now was officially a girl. The story was national news because parents were rightly upset when they found out.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/transgender-reveal-kindergarten-class-rocklin-academy-parents-upset/

It’s stories like this that give me trust issues with strangers teaching my children.

To protect my children from exposure to pornography.

There are way too many scary stories out there of young (emphasize: young) elementary school students bringing porn to school on their smartphones. A teacher friend of mine told me about a big to-do at her school a few years ago because one girl was showing pornographic videos to other kids at recess and bullying them to not tattle about it. What a disaster, and what a scary and unsettling first exposure to this kind of thing for a child.

Now, don’t get confused or put words in my mouth. I am not saying, “I want my kids to be naïve and totally stupid about the evils of the world; I don’t want them to even know that pornography exists because I want to protect them from it so completely! I’ll just lock them away in a homeschool-tower and cut off all their contact with the outside world!” That’s not what I’m saying at all.

I’m saying this: in this world, my children being exposed to pornography is not a matter of if, but when. That’s a scary sentence both to write and to accept. Part of my job as their parent is to prepare them for that day when they do come across pornography, to teach them what to do, who to talk to about it, and how to move forward. I want to have that hard, but necessary conversation with them prior (and often) to any exposure so they are prepared and not shocked.

To be free to talk about religion and Gospel topics without fear.

This will probably apply more to older kids and more complex topics (perhaps–you never know). But if lessons or books or ideas spark Gospel-related questions, then we’re free to take a detour and discuss that as well. We can talk about religious holidays, other religions, religious history, the church’s political stances, and so on, all without that vague “separation of church and state” misconception that teachers have to hide behind.

Personal:

So my boys don’t grow up feeling like they have to conform in order to be “cool.”

So my boys don’t emotionally suffer from not living up to outside standards of perfection.

So my boys can discover and express themselves freely and openly without peer pressure.

So my boys don’t have to mentally and emotionally heal from the scars public school so often afflicts.

I don’t want you to walk away from this article thinking that I’m emotionally traumatized and damaged or anything like that strictly because of public school (actually, go ahead and think that if you want; we’re all emotionally damaged in some way). But when I honestly look back and reflect on my life and what negatively influenced me the most, I’d have to say the answer is school.

I certainly had some unique circumstances that led to this conclusion, but it remains my conclusion nonetheless. And one of the biggest factors that dictated my personality was concepts like the above mentioned issues.

I had to be “cool,” always and constantly. I promise you I most certainly wasn’t, but the pressure to be so was very real and very overwhelming. And my many failures at being cool were like emotional gut punches over and over again.

I couldn’t express myself. It would bring too much attention to me.

I couldn’t ask questions. It would seem like I was pushing back against the authority of the teacher. Or people might think I was stupid.

I couldn’t be passionate about anything. It was too nerdy. That’s why I didn’t have almost any friends in seventh grade, because I spent nearly every Friday night watching Star Trek and then writing my (very cheesey) novel, all in the utmost secrecy. I lived in terror of my school friends finding out I was so nerdy and mocking me forever because of it. I literally became a different person when I went to school, locking away my secret interests.

I couldn’t mess up or get anything wrong, not ever. Often, unfortunately, that meant I shouldn’t even try something new, at least not in the public eye of school, for fear of failing in front of all my peers. And note that the failure itself wasn’t the issue here, but the failure in front of my peers.

I couldn’t think, speak, dress, or behave outside the box because that’s social suicide, right?

After years of that, it really took a toll. I remember multiple times wishing I’d spoken up in class about something, but didn’t think it was acceptable. I remember wanting to share something I loved with my friends, but I was too afraid to. I remember having to feign indifference when I really was desperate to know more about a topic because I didn’t want to seem uncool.

And so cemented that mentality into my personality, and it’s been something I’ve struggled to overcome all these years later. I have to always appear “cool” and put together; I can’t ever be confused or unsure of myself. I have to always know the right answer; I can’t ever be taken aback by something or thrown off. That’s not “cool.”

And then I think of my boys. Is that the mentality I want them to grow up with? Is that fear-based conformity what I want to mold their personalities?

When researching homeschooling, I came across the same argument and rebuttals all the time: “What about socialization?”

But it’s true: What about socialization? Because that’s how public school socialized me: I was scared and shamed into sitting down, shutting up, and conforming to the masses so as not to stand out.

Thanks a lot, public school.

Now imagine the beautiful freedom my boys, or any child, could have without those restraints? Homeschool is a great place to practice truly not caring what other people think about you. You can be free to be passionate and excited, to think freely and question anything without judgement, and to follow your own interests without the pressure to sit down, shut up, and conform.

And the conformity wasn’t the only emotional issue I suffered because of public school.

I remember having this conversation with a close friend recently and he claimed that his religion forced these horribly unhealthy perfectionist ideals onto him and how he’s since suffered because of it. We share the same religion, but I never felt the same pressure to be a perfectionist from my church–instead I felt it from school. But yes, I’ve similarly suffered because of it.

Do you remember above when I spoke about how stressed I was about my grades not being perfect? I believe that’s the basest root of my dangerous and crippling perfectionism. Religious perfection isn’t measurable because so much religious devotion is internal. But academic perfection? Oh, it’s total achievable in that perfect 4.0, and I somehow always managed to just miss that mark. That’s why I was so devastated by my 3.8, because it meant I wasn’t perfect when so many of my peers were.

Ouch.

The short of it all? I’ve had to do a lot of emotional and mental healing from a lot of my public school experiences. I don’t at all claim that homeschooling would save my boys from any and all emotional scars, but if I could save them from the experiences I had, then I most certainly would.